Lake Hawassa is what happiness looks like

What would happiness look like?

Over a hundred stakeholders were invited to participate in workshops which were hosted by the Rift Valley Lake Basin Development Office, GIZ and SIWI. By piecing together individual perspectives and understanding, one could draw a bigger picture of the present scenario and achieve shared understanding of what was needed in the future.

This is the source-to-sea approach which uses a structured interactive process with the aim to have as broad a representation as possible in decision-making. An endorheic lake, like Lake Hawassa, is much the same as a sea, capturing everything that flows into it. The dynamics are comparable, but everything happens at a smaller geographic scale. “It is a lot easier to build a picture of the entire biophysical and governance landscape with the help of the stakeholders”, according to Mathews.

This is the source-to-sea approach which uses a structured interactive process with the aim to have as broad a representation as possible in decision-making. An endorheic lake, like Lake Hawassa, is much the same as a sea, capturing everything that flows into it. The dynamics are comparable, but everything happens at a smaller geographic scale. “It is a lot easier to build a picture of the entire biophysical and governance landscape with the help of the stakeholders”, according to Mathews.

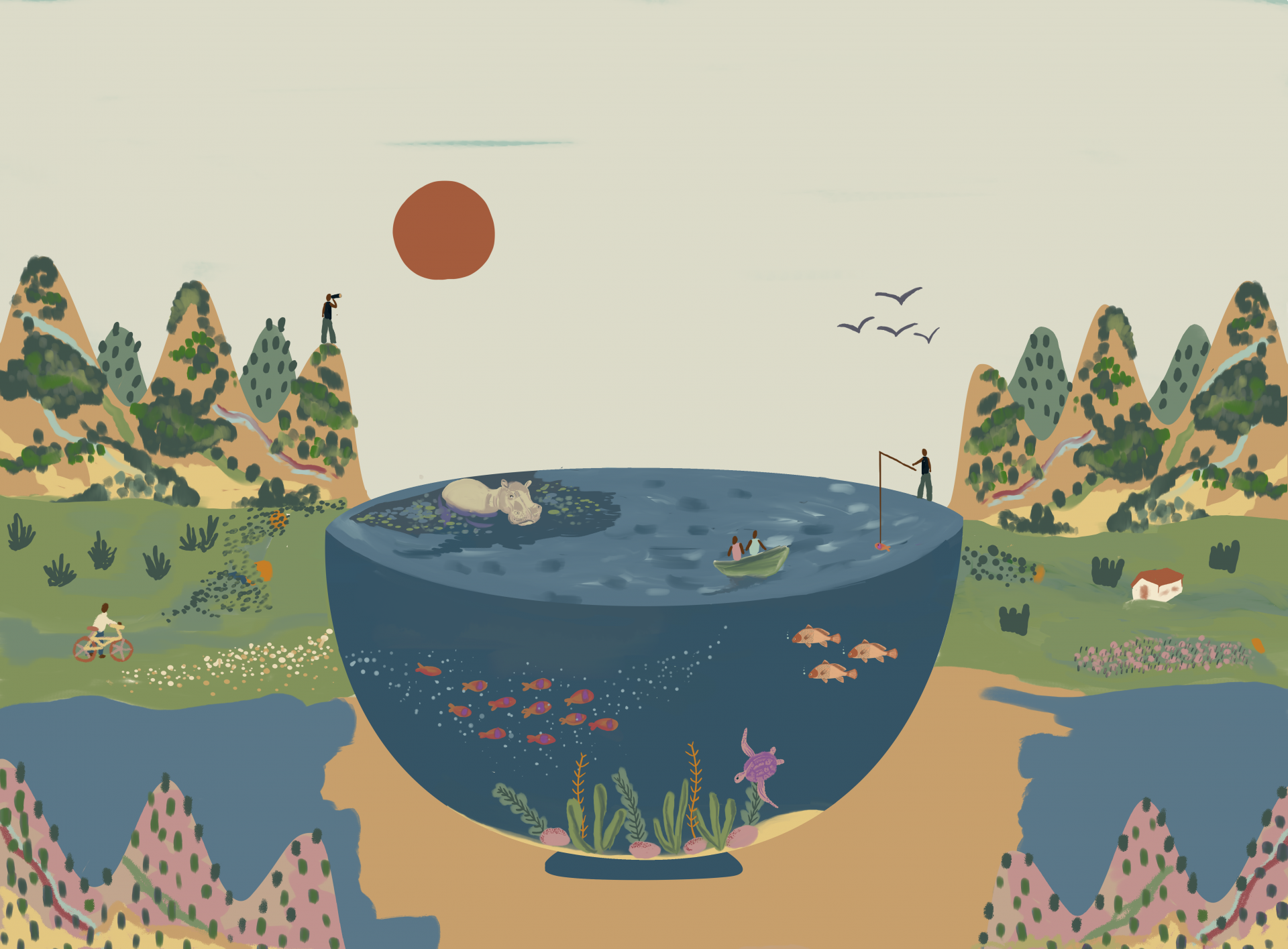

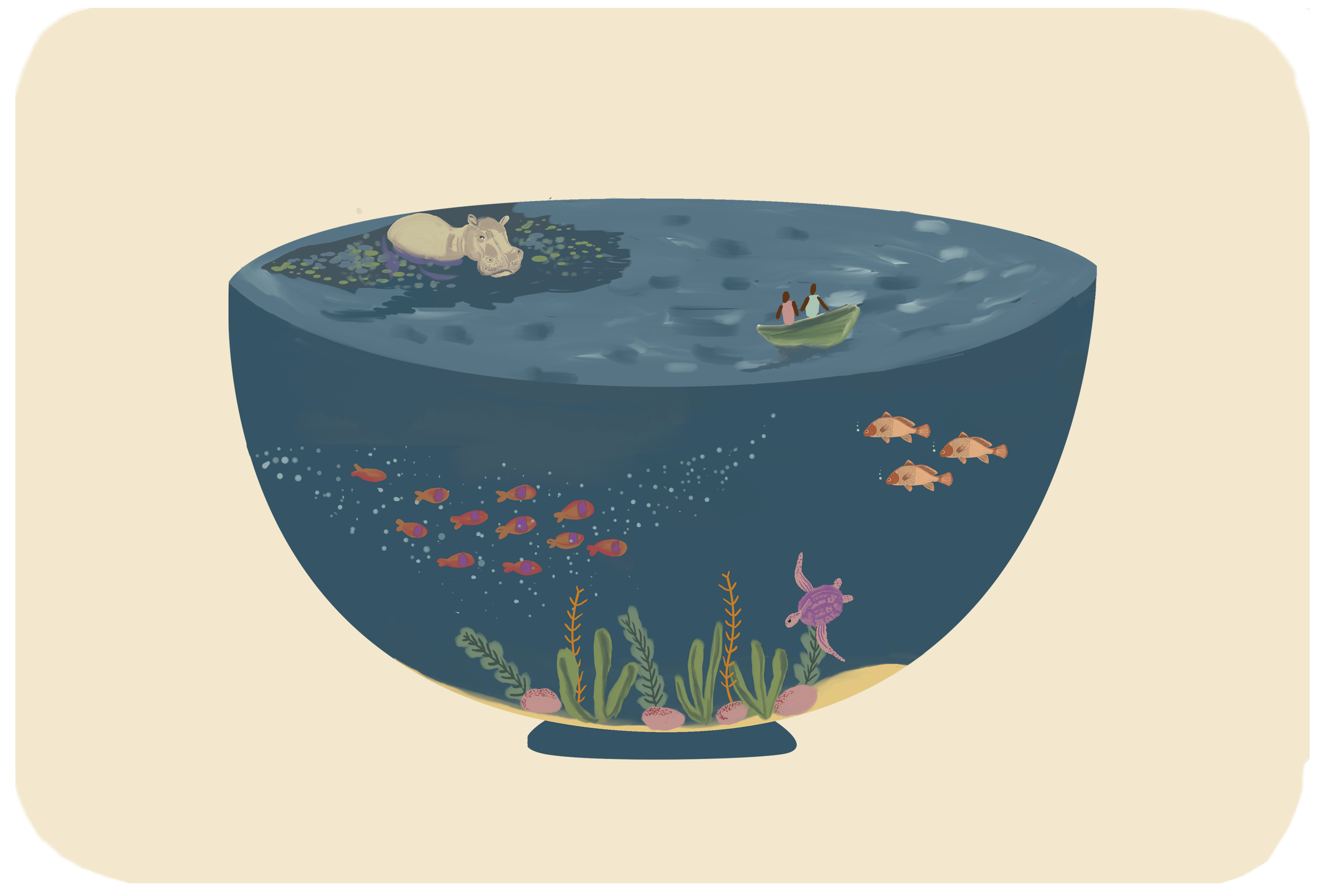

One of the questions up for discussion with participants at the 2019 workshop was ‘What would happiness look like?’ The answer was simple – A healthy lake forever. One that is free of unwanted sediments for an ongoing vibrance of fishery and tourism industry around the lake. Participants discussed the behaviour and practices that needed to change in order to get there. For example, which policies were effective or where was implementation lacking when it came to sediment and plastic waste management, and what kind of finance and capacity were needed? More importantly, what were perceived individual roles and responsibilities and which problems needed collective action? This would be followed with an action plan for monitoring and evaluation.

Picture perfect

The pilot to implement the source-to-sea approach for Lake Hawassa was completed in 2025 after facing several barriers in logistics pertaining to the Covid-19 pandemic and a cut in funding. In 2024, countries had signed a legally binding agreement to end plastic waste. But how can one successfully do that?

Several answers were to be found in the success of Lake Hawassa’s source-to-sea pilot. The pilot had shepherded local stakeholders to build a trusting and transparent coalition to understand their own roles and responsibilities in preventing plastic pollution, and also interdependencies.

In 2030, a Water-Energy-Food-Forest Nexus Agency was set up for the Rift Valley Lakes Basin. Upstream activities are managed in collaboration with experts working on lake ecosystem health. Enhanced practices of agroforestry ensure maximum crop production while preventing soil erosion. Hawassa was among the first places in the Rift Valley to set up solar powered panels in individual homes, lifting the pressure on forests from fuelwood collection. It was also among the first to have advanced technology for managing solid waste, part of which also served as biofertilizer for agriculture.

In 2030, a Water-Energy-Food-Forest Nexus Agency was set up for the Rift Valley Lakes Basin. Upstream activities are managed in collaboration with experts working on lake ecosystem health. Enhanced practices of agroforestry ensure maximum crop production while preventing soil erosion. Hawassa was among the first places in the Rift Valley to set up solar powered panels in individual homes, lifting the pressure on forests from fuelwood collection. It was also among the first to have advanced technology for managing solid waste, part of which also served as biofertilizer for agriculture.

In 2050, the impact of cross-sectoral interventions to restore the lake basin’s landscapes is clear. The region is not only famous for its healthy hippo population but also its enormous fishing markets. Tourists visit the Rift Valley to see the most scenic and litter free lake ecosystems. Among several museums including those about the first humanoids that walked the Valley, a favourite is the one in Hawassa. It houses sculptures made from the last remains of single use plastic cleaned out from Lake Hawassa and other surrounding lakes.

Explore the entire series

‘Visions of water – seeing the unseen’ is a series of illustrated stories that imagines our world in 2050. The previous story explores the power of water to strengthen food security.

Read all stories here