New framework on water governance for practitioners

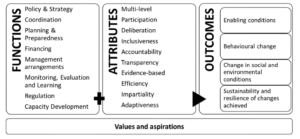

Water governance is thus described as a combination of functions, performed with certain attributes, to achieve one or more desired outcomes, all shaped by the values and aspirations of individuals and organizations.

Additionally, the authors present an example showing how this framework can be implemented in practice through a water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) diagnostic and planning tool. The WASH Bottleneck Analysis Tool (WASH BAT), was developed by UNICEF, with input from SIWI, to improve the efficiency of the WASH sector, and is based on the water governance functions and attributes defined in the framework.

The framework will enable water practitioners and policy makers to understand how action-oriented water governance processes can be meaningfully designed, and ultimately how to strengthen water resources management and services. It also provides a fresh insight and guidance for young water professionals, researchers and academicians, by introducing water governance from concept to practice.

To assess the existing gaps and improve water governance, one must first understand the governance functions and attributes and how they are interrelated, along with how values and aspirations of individuals shape this process.

Water governance functions

Water governance functions is defined as the core activities or processes necessary to develop the sector that are assigned and undertaken by a specific organization (e.g. a ministry or a basin authority).

It is important to consider that there may be both commonalities and differences of activities within each function, across the areas of water and sanitation, water resources or transboundary waters. There is no pre-defined sequential order of implementation of the functions as it may vary depending on the context. For instance, sector policy and strategy are usually established before proceeding with activities on planning and coordination but there might be cases where the service delivery may still need to function on a daily basis while the policy and legal frameworks are under discussion.

Water governance attributes

Water governance attributes describe how the governance functions are performed. For example, participation is a key attribute that implies not just mere presence but meaningful and active involvement of a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including vulnerable or marginalized groups in decision making processes.

Another attribute is inclusiveness, recognizing the rights of individuals and groups across different categories, needs and vulnerabilities, and without any kind of discrimination based on race, colour, age, gender, religious affiliation, ethnicity, language, disability, economic backgrounds or any other conditions of origin. For some of the attributes such as participation, and multi-level governance structures to be effective, they must be in coherence with other attributes such as having accountability mechanisms in place. Accountability refers to the principle whereby elected officials and those that have a responsibility in water services or water resources management account for their actions and answer to those they serve.

Four Orders of Outcomes

- First: Creation of the enabling conditions for a governance initiative.

- Second: Behaviour change of resource users and key institutions.

- Third: Achievement of desired changes in societal and environmental conditions.

- Fourth: A resilient social-ecological system where desired conditions are sustained.

Adapting the Orders of Outcomes framework proposed by Stephen B. Olsen for the governance of source-to-sea systems, the authors explains four ‘orders’ that lead to the ultimate long term goal of sustainable forms of development. Further highlighting that the desired outcomes is interlinked to the performances of the core governance functions and how it is conducted (attributes).

Values and aspirations of stakeholders

The quality and extent of implementation of the functions will be shaped by the values and aspirations of the stakeholders in the governance process, including decision-makers and citizens. Part of this involves raising awareness of the challenges involved and trying to influence people’s behaviour. Frequently cited examples include the efforts to reduce water consumption during the Cape Town water crisis in 2017-18 and the Clean India Mission, often described as the world’s largest toilet-building and behavioural change initiative. Similarly, if stakeholders embrace integrity, i.e. a moral and ethical value of professionalism, honesty and transparency in their governance functioning, corruption in the water sector will lessen.