Water cooperation innovations to contribute to accelerated implementation of the 2030 Agenda

A new Water Cooperation Global Outlook Report, developed by the International Centre for Water Cooperation (ICWC) and SIWI, due to be published in the autumn of 2023, will provide a global assessment of water cooperation preparedness, with a special focus on African basins. A Working Paper, detailing some initial insights, was launched during this year’s World Water Week.

Many countries are facing increasing challenges related to water, whether in the form of too little, too much, or too polluted water. Water scarcity, water-related disasters, and extreme weather events – such as floods and droughts – and inadequate climate change mitigation and adaptation, continue to rank among top global risks as assessed in the Global Risk Report by the World Economic Forum (2022).

“Cooperation among stakeholders across sectors and borders is key to meeting these water challenges. While cooperation on water issues does take place, despite the ubiquitous frame of water as a source of conflict, it tends to be fragmented and severe cooperation deficits and policy misalignments still exist,” says SIWI’s Håkan Tropp, who moderated the World Water Week session, Water Cooperation for accelerated implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, on 20 August 2023. A synopsis of which can be read here: The crux of effective water cooperation, from the experts.

Cooperation between stakeholders, across sectors and scales, will likely become increasingly important as water pressures intensify, water management becomes more dynamic (through the adoption of integrated and coordinated approaches), and from the rising complexity of actors involved in water management. Further, the cross-sectoral nature of water challenges and the current struggles of many decision-makers and managers in the water sector, such as demographic changes, increasing water demands, and the impacts of climate change, also speak for the growing importance of cooperation.

Taking many different forms, water cooperation includes: the factors of governance, leadership, financing, joint programming and investment, data and information, and the existence of an enabling environment. All play important roles for how well-positioned or prepared countries and basin organisations are for water cooperation across international, national, and subnational jurisdictions, and across sectors and stakeholders. The Water Cooperation Global Outlook Report, currently in production, puts these factors at the centre of an assessment of the status and trends in water cooperation at different scales. The report has two components:

- a global assessment of national and sub-national level water cooperation preparedness, and

- a special focus on Africa, in the form of a water cooperation assessment in 32 river basins in Africa.

Initial insights from the Water Cooperation Global Outlook Report, are presented in the Working Paper “Water Cooperation for Accelerated Agenda 2030 Implementation: Special focus on transboundary water cooperation in Africa”.

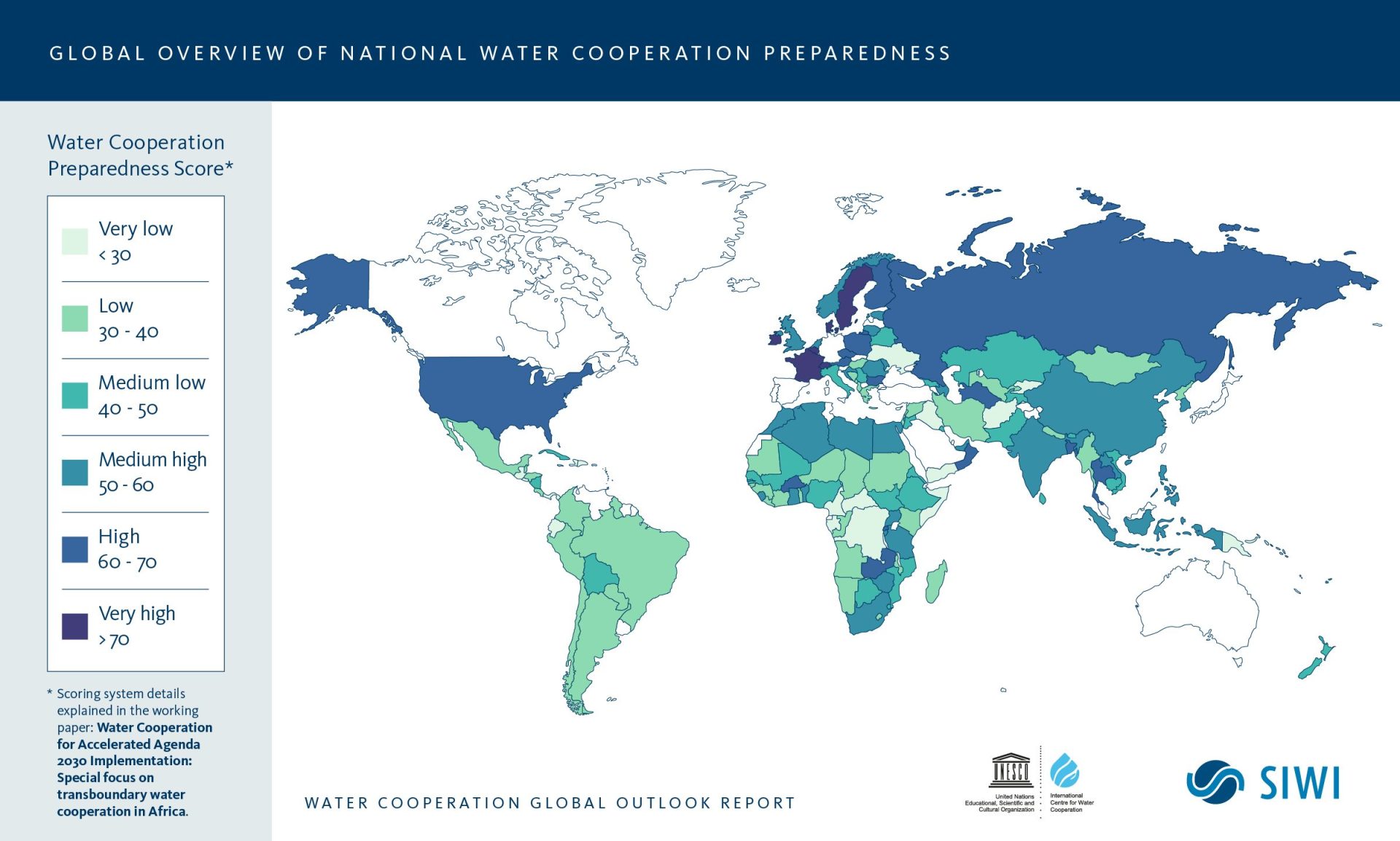

The global level assessment of water cooperation indicates that a deficit in water cooperation preparedness exists worldwide, and that there is substantial room for its improvement in most countries. There are considerable differences in water cooperation preparedness both between countries, and between and within regions. On average, countries in Europe are better-positioned while countries in Oceania and the Americas least well-positioned. Many small island developing states (SIDS) also score low or very low on cooperation preparedness.

The largest differences between countries in the same region are in Europe and Asia, and to a slightly lesser extent, Africa. Another insight is that while countries with higher income levels often have relatively high water cooperation preparedness, this isn’t a deciding factor, as countries with lower income levels can also be well-prepared. This is a particularly positive observation, since it suggests most countries have the potential to implement improvements in domestic and international water cooperation.

The analysis and discussion of the 32 African river basins suggests three key features for building long-term resilient and incremental transboundary cooperation.

Gradualism is an important factor to temper expectations and keep ambitions in check.

Pragmatism could be beneficial, when an agreement for international cooperation may not meet all interests of each state involved but is still recognised as being beneficial overall and therefore accepted.

Outside support can play a crucial rule in overcoming large power differences between countries; technical advice, organisational development, or training courses for staff, for example, can help to reduce the risks of imbalanced relationships within a basin.

A factor related to all these key learnings is the centrality of the role of trust in promoting cooperation. Trust implies accepting a certain degree of risk, in the belief that a better outcome will result. Countries, represented by individual government officials, need to establish small gains which allow them to establish and build productive relationships with their counterparts – at the level of the individual.