Why landscapes are critical to climate policy

The role of landscapes receives a lot of attention at the climate meeting COP25, with a special event about the IPCC Climate Change and Land report. Contributing author Anna Tengberg, from SIWI, was interviewed in WaterFront magazine about how to work with resilient landscapes.

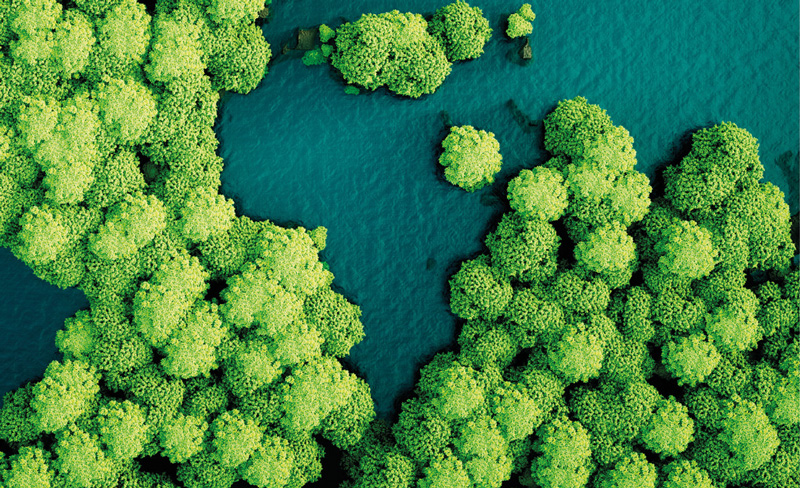

Never before have humans used so much land and freshwater, and we are only now starting to understand the consequences. According to the recent Climate Change and Land assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human use affects more than 70 per cent of the global, ice-free land surface, which has led to growing net greenhouse gas emissions.

At the same time, the report shows how landscapes also serve as carbon sinks and that sustainable landscape management is a powerful tool to make societies more resilient to climate change. Countries are starting to realize that we’re at a crossroads, where sustainable landscape management must be used for both mitigation and adaptation, while inaction may soon result in a vicious circle that will be hard to break.

In the worst-case scenarios, emissions from agriculture, forestry and other forms of land use will rise sharply (currently they account for around 23 per cent of human-induced emissions). A main driver could be increased demand for farmlands, as human populations grow rapidly while soils become increasingly degraded and less productive. A likely response would be to turn more forests and wetlands into cultivated land, meaning that they become carbon emission sources instead of carbon sinks. The result would be higher emissions of greenhouse gases, more soil erosion, more unpredictable rainfalls, more droughts and floods.

In these scenarios, ecosystems are becoming increasingly fragile, with landscapes less able to provide food, freshwater, buffers and other vital ecosystem services. According to the Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) this can drive one million species to extinction and threaten human existence.

“The situation is very serious. But we may be at a turning point, with more people becoming aware of the climate crisis and how it is linked to ecosystems. I hope that governments will understand that sustainable landscape management must be at the heart of effective climate policy if we are to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement,” says Professor Anna Tengberg from Lund University, Sweden, and Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI).

As a contributing author to the IPCC report on Climate Change and Land she has looked at what keeps countries from making the necessary changes. Lack of knowledge turns out to be an important barrier. At times, the right information is not available, for example about to which extent specific soils or forests are degraded. In other instances, different studies point in different directions – will for example 90 per cent of coastal wetlands disappear or will they in fact increase in size? It is also hard to predict how different factors influence each other and to foresee cascading effects.

Even when the scientific information is available, it can be so complex that decision-makers find it hard to understand and act upon. Many countries struggle to formulate policies, laws and regulations, others have problems implementing them or following up to draw conclusions.

So, while all countries have a responsibility to do what they can to mainstream sustainable landscape management into all areas of policymaking, Anna Tengberg stresses that the international community should provide support. For best-practice ideas to spread fast enough, countries and organizations must collaborate over funding, knowledge, research and networks. “We all benefit from swift action and we all pay a high price if we don’t act fast enough,” she says.

One complex and contentious topic is the relationship between trees, forests and water. Researchers agree that there are important interlinkages, but they still don’t fully understand exactly how trees and forests protect and regulate water. There is a need for more research, monitoring and evaluation of the effects of forest management and land use change for water yields and quality. But interest is growing, resulting in many new tools and methods that benefit the science community and practitioners alike.

One example is the Blue Targeting Tool, first developed in Sweden back in 2011 but now used in many different contexts. Aline Fransozi, PhD student at the Forest Hydrology Laboratory of Sao Paulo University in Brazil, has worked on adapting it to tropical conditions. “The biggest challenge is the high biodiversity and natural heterogeneity found in tropical areas. We have many knowledge gaps and lack the calibration needed for making comparisons.”

The adaptation of the Blue Targeting Tool is still a work in progress, but Aline Fransozi hopes that it will soon be used to close some of these knowledge gaps. “We believe that this tool, just like the original, will be used also outside of universities, by landowners, organizations and public institutions, to guide the management of degraded riparian areas,” she says.

Another project that has been met with great interest is the Nairobi Water Fund. It started in 2015 with the aim to conserve the Upper Tana watershed that produces 95 per cent of water for the Kenyan capital and 65 per cent of the country’s hydropower. “The Nairobi Water Fund has been a triple-win initiative through its three goals, the 3Cs: Conserving nature, Clean water and Community benefits,” explains the Water Fund’s Director, Fredrick Kihara.

The Fund is working with over 20,000 small holder farmers in the watershed who are practicing agroforestry and planting up to two million trees to prevent erosion, which used to be a big problem in this area characterized by steep hills. As a result, Nairobi now receives cleaner water and the hydropower plants can operate more efficiently when there is less sediment. Not least, the massive planting of trees, grass and plants is expected to result in the absorption of 320,000 tons of carbon, annually.

Local farmers have also received more immediate benefits. “The project has initiated rainwater harvesting by developing smallholder water pans for storage. This is helping to reduce over-abstraction of water during the dry season to support irrigation and an increase in food production,” says Fredrick Kihara.

Stockholm WaterFront, no 3 2019

Sign up for your FREE subscription of Stockholm WaterFront here >>