- SIWI – Leading expert in water governance

- /

- Latest

- /

- The Clean India Mission: world’s largest sanitation initiative

The Clean India Mission: world’s largest sanitation initiative

In the past few months, many villages in India have organized a Gaurav Yatra, a walk of pride, to celebrate that they have been declared Open Defecation Free (ODF). This is part of the government-led Clean India Mission, the world’s largest toilet-building and behavioural change initiative.

Open defecation is one of the world’s greatest health risks and a leading cause of child mortality, which is why the United Nations want the practice stamped out by 2030. Five years ago, India was home to 60 per cent of the world’s open defecators, but the government claims that this number has been drastically reduced under its Clean India Mission programme, also known as the Swachh Bharat Mission.

In 2014, when the campaign was announced as a People’s Movement to end open defecation, fewer than four in 10 rural Indian households owned a toilet. By the end of the programme, in connection with Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th birthday on 2 October 2019, official figures put coverage at 100 per cent.

The programme was implemented by the state governments, with support from the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. More than 100 million toilets have been built across rural and urban India since the launch of the mission. Social and behavioural change communication has been a large feature of the programme, with a number of nationwide campaigns in traditional media as well as on social media.

The campaigns focused on debunking myths and misconceptions about the construction, maintenance and use of toilets, encouraging people to build toilets, but also to challenge the social belief that only women, the elderly or sick family members should be using them. Public figures, including famous cricketers, actors and politicians, have been engaged as ambassadors for the campaign. Trained grassroot level volunteers called Swachhagrahis, “Ambassadors of Cleanliness”, played another important role, assisting in the construction of toilets as well as in campaigns and monitoring.

Other incentives were also used. Villages declared Open Defecation Free get extra funds from the state government and officials from successful districts received official rewards and recognition.

Professor Val Curtis, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, argues that behavioural change at decision-making level has been just as important as the changes seen at community level. She interviewed national and local government staff and found that senior political support and disruptive leadership led to changed behaviour among decision-makers and that this made them more credible among the general public.

The campaign is widely seen as a success and the Bill & Melissa Gate Foundation felt it made India’s prime minister Narendra Modi worthy of its Global Goals Award. According to a study commissioned by the Gates Foundation, the programme seems to not only have led to a large number of toilets being built but to people actually using them.

The programme, and the Gate Foundation’s support for it, has however also been questioned. In November, the Indian National Statistical Office’s released its survey on sanitation, with lower levels of household coverage than the official numbers. According to the survey, only 71 per cent of households had access to toilets at a time when the Swachh Bharat programme claimed it was 95 per cent.

Human Rights Watch and other organizations have however warned that the methods for creating social disapproval can lead to downright human rights abuses, especially against marginalized groups like Dalits and Adivasis. The topic has been hotly debated after two children were killed in September for allegedly defecating in the open, causing the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation to issue a statement condemning coercion as a method to achieve the goal.

The children were Dalits and in an article in Ideas for India, researchers Diane Coffey and Dean Spears from the Research Institute for Compassionate Economics, RICE, emphasize that questions related to India’s outlawed but prevailing caste concepts are central to understanding the issue. “Untouchability and social inequality are important parts of why open defecation continues,” they write. Poor families are most likely to be shamed and punished for open defecation but may not be able to afford to build a latrine.

Coffey and Spears raise the question if the goal to end all open defecation within five years was in fact too unrealistic and if this can have triggered some people to either tinker with statistics or to accept draconian measures. They write: “The other foreseeable consequence of an extreme goal is to legitimise extreme methods. And in a country in which nearly a third of households admit to practicing untouchability (Thorat and Joshi 2015), it is not a surprise that when local government officials sanctioned coercion and intimidation as means of achieving Swacch Bharat, the consequences would fall most heavily on the already disadvantaged.”

The Indian government, on the other hand, has dismissed the comments made by Coffey and Spears as “misleading” and “outrageous”, and points to reports from UNICEF and others about health benefits from the campaign. In a press brief in January 2019, the government’s press bureau states that the statistics regarding toilet coverage have been independently verified in India’s massive National Rural Sanitation Survey. The government also notes that Swacch Bharat has been acknowledged by Cass Sunstein, one of the inventors of nudging, as a good example of positive behavioural change.

This text was first published in WaterFront 1/2020 – read the full magazine here.

Global water issues in your inbox

Stay up to date on SIWI's work and related topics from around the world.

Sign up to our newsletterMost recent

Water and land: Partners in climate mitigation

- Water in landscapes

- Wetlands

- Water governance

Taking root: locally driven forest landscape restoration

- Water in landscapes

- Wetlands

- Groundwater

- Resilience through water

Reflections from World Water Forum

- Water governance

Groundwater: How to better protect this hidden treasure?

- Groundwater

- Water in landscapes

SIWI Amman and UNICEF host Libya representatives for WASH exposure visit

What is the role of water in rural and urban school facilities?

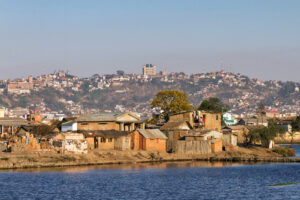

Identifying bottlenecks to water governance in Madagascar