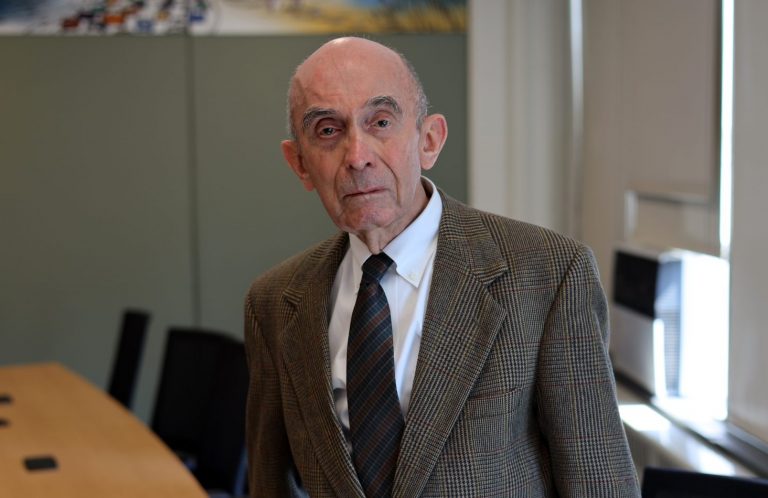

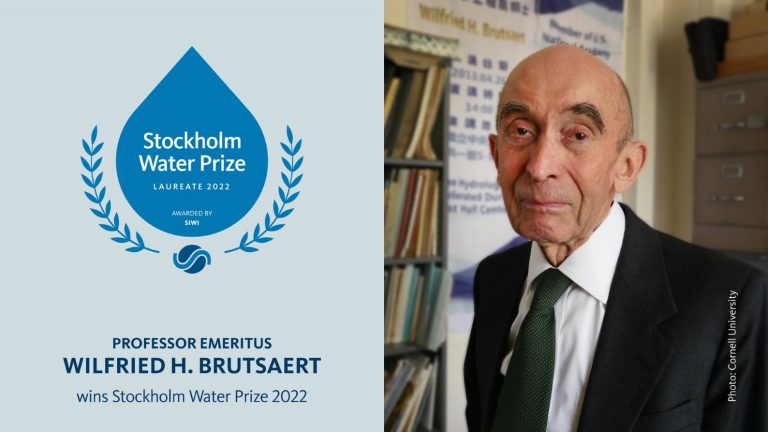

7 questions to Professor Brutsaert, Stockholm Water Prize Laureate

Global water issues in your inbox

Stay up to date on SIWI's work and related topics from around the world.

Sign up to our newsletterCongratulations on the 2022 Stockholm Water Prize, what does it feel like to receive this award?

It is very nice and very gratifying indeed; I am very grateful for this. In a way I guess I should be most grateful for my former students; it will tell them that they did not totally waste their time working with me. So, thank you, very, very much.

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

I was born in 1934 in Ghent, Belgium, as the oldest of six. When I was six years old, the war broke out and it finished when I was ten. Since that is the time when children learn to read and write, I was very much aware of what was happening, and this affected my early years profoundly. My primary and secondary education in Belgium was of a classical nature, which meant that I studied Dutch, French, German, Latin, and classical Greek before I got a chance to study English. So my English was rather marginal and to compensate this, when I was a university student during summer vacations I went to the UK to take part in several agricultural camps. Then back at the university in Ghent, I was fortunate enough to get to know an American professor, Don Kirkham, on a sabbatical and that eventually led me to go to the USA to one of his former students to study irrigation at the University of California at Davis. Initially my dream was to work in water development for the United Nations or some similar organization but I ended up studying for a Ph.D. instead.

You have published on a broad range of topics but are perhaps most well-known for your game-changing work on evaporation. Can you explain what this is about?

Evaporation is one of the main components of the hydrologic cycle, but it is difficult to measure or to estimate in the absence of direct measurements. I have however found that available estimation methods could be improved by incorporating developments in atmospheric turbulence and its interactions with the Earth’s surface energy budget. Some of these findings have subsequently been used to initiate better measuring technologies, both by remote sensing and terrestrial observations, to assess evaporation. They are therefore also relevant for climate modeling and, conversely, in attempts to estimate the effects of climate change on the water cycle.

You joined the faculty of Cornell University in 1962 and stayed on for more than 50 years. How did your field of research change during that time?

Primarily I witnessed three major changes, namely in instrumentation, in computation, and in the understanding of climate and the environment.

When I started, we had traditional thermometers and cup anemometers for wind speed and we were measuring precipitation with bucket-like rain gauges. By today’s standards, the instruments were somewhat primitive and many measurements from early last century are in fact unreliable.

And then there is computation. When I joined Cornell, we had three computers and they were enormous in size. Now I can sit with a small laptop in our kitchen and that has made it possible for me to keep working after retirement even during the pandemic. But more seriously, advanced computing with general circulation models has allowed us to take great strides in better understanding the water cycle.

The third change is the growing interest in the environment, Earth science, and the climate. When I was invited to join the faculty at Cornell, the main concern in this regard was water supply and water resources; the university had just founded the Water Resources Institute, but some ten or so years later this concern evolved more broadly into environmental sciences.

Will you come to Stockholm to receive the Stockholm Water Prize from the hand of His Majesty the King Carl XVI Gustaf in August?

Of course, that will be an honor and a great pleasure.

The royal award ceremony will take place as part of World Water Week. This can be seen as very timely that you receive the Prize this year since the Week’s focus is on unseen water, such as evaporation and groundwater. Why is it important to raise awareness of this invisible water?

The unseen water is not only unseen but has historically been unmeasured. It has therefore been the largely unknown component of the hydrologic cycle and we need to close this gap. We need to understand the role of evaporation and groundwater to protect the freshwater that we have. I find it tremendous that SIWI is paying attention to this.

What would you like decision-makers to do?

The main task is to keep water clean. I strongly feel that the people in charge cannot be severe enough in imposing the strictest possible rules and sanctions here. Having clean water is crucial for the survival of humanity.