The year is 2050. People and planet are thriving in peace and prosperity. How did we get here? A world where all the Sustainable Development Goals of 2030 have been realised. This series of illustrated stories imagines ‘visions of water’ inspired by real world projects and partners of SIWI. We imagine a future when we have recognised the unseen powers of water.

This third piece in the series explores the power of water to strengthen food security.

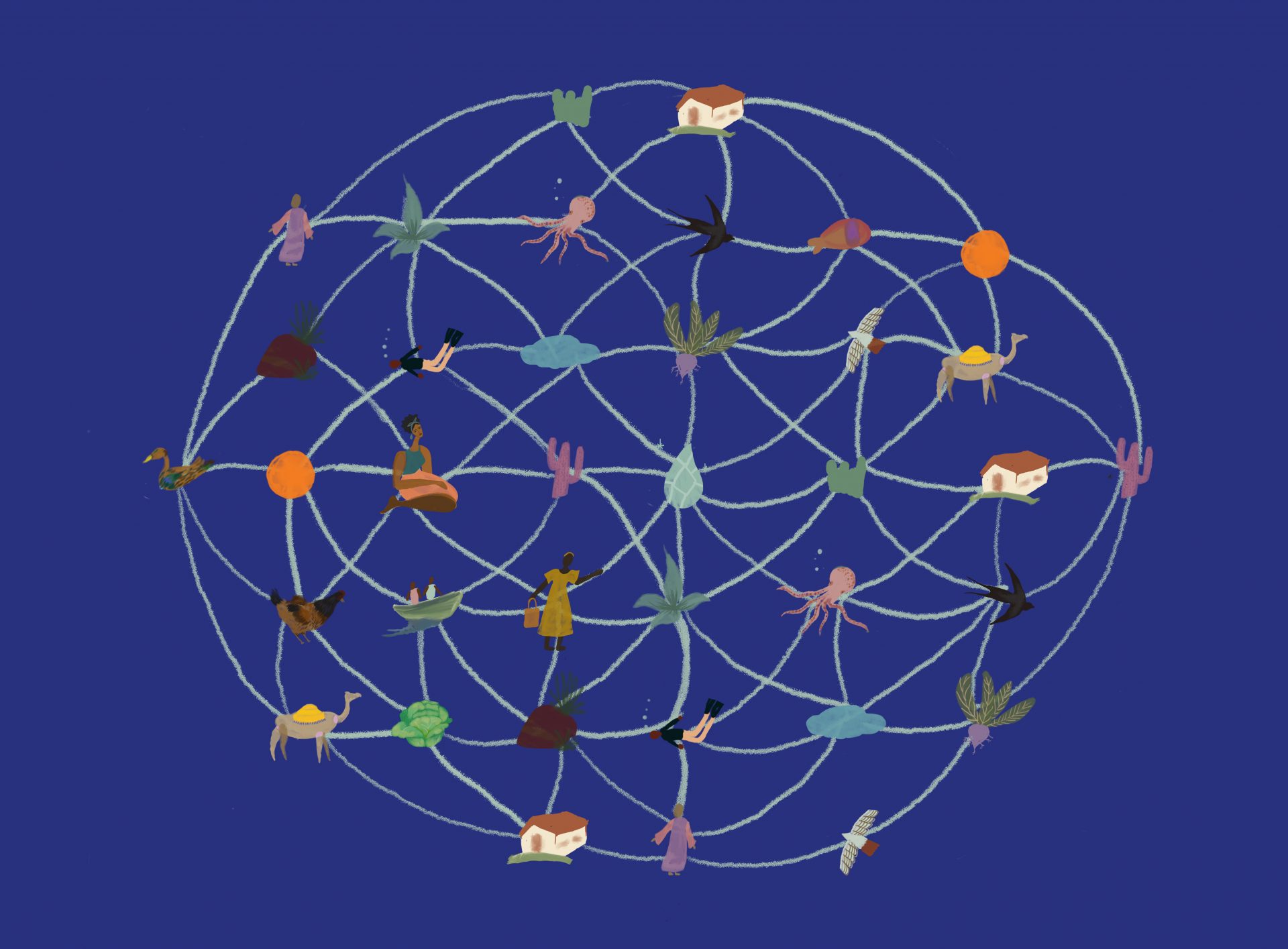

What type of water is needed for growing food? Are farmers doing enough to secure those sources of water? Are food value-chains supportive of those farmer practices? As it turns out, it takes a whole inter-governmental system to ensure that.  Today, in 2050, the Zambezi Watercourse Commission is investing big to support rainfed agriculture across the basin’s eight countries. The project Transforming Investments in Africa’s Rainfed Agriculture has contributed to the success, thanks to an understanding that irrigation investments alone could not solve food shortages. A different approach was needed to rethink investments.

Today, in 2050, the Zambezi Watercourse Commission is investing big to support rainfed agriculture across the basin’s eight countries. The project Transforming Investments in Africa’s Rainfed Agriculture has contributed to the success, thanks to an understanding that irrigation investments alone could not solve food shortages. A different approach was needed to rethink investments.

Africa can have its food and eat it too

Until the 2020s Africa was spending billions of dollars to import food to the continent, while exporting much of its own produce – more than the entire amount of development aid received by the continent. “That’s a crazy situation if you think about how much arable land was available”, said Anton Earle of SIWI at the time. Back then, more than half of the young population in the Zambezi region was working in the agricultural sector. Not out of choice. It was hard work with little commercial scope beyond providing food for one’s own family.

Also, during the same era that had fuelled a masculine vision of water engineering, the link between water and food was being lost. The simple practise of harvesting rainwater or maintaining soil moisture to protect crops, was overtaken by the idea of irrigation. What was the result? While nearly 95 per cent of Africa’s agricultural land was rainfed in the 2020s, 95 per cent of public agricultural water investments were pumped into irrigated agriculture. In other words, only 5 per cent of the money was devoted to rainfed agriculture.

The ‘tiara’ over Africa’s food

In 2022, Earle noted that rainfed agriculture was seen as a little backward and traditional and that governments were viewed as more powerful if they pushed for large-scale irrigation schemes. The Transforming Investments in Africa’s Rainfed Agriculture (TIARA) project however, had not been shy of advancements in technology. The opposite, in fact. TIARA capitalised on enhancing existing rainfed agricultural practices such as terracing, mulching, Zai pits and sand dams, to attract finance. The project was initiated by SIWI in 2018, in partnership with the Stockholm Resilience Centre and the Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa.

In 2022, Earle noted that rainfed agriculture was seen as a little backward and traditional and that governments were viewed as more powerful if they pushed for large-scale irrigation schemes. The Transforming Investments in Africa’s Rainfed Agriculture (TIARA) project however, had not been shy of advancements in technology. The opposite, in fact. TIARA capitalised on enhancing existing rainfed agricultural practices such as terracing, mulching, Zai pits and sand dams, to attract finance. The project was initiated by SIWI in 2018, in partnership with the Stockholm Resilience Centre and the Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa.

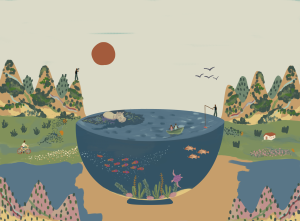

The solutions recommended by TIARA are climate-smart and consider “farmers as our front-line water managers” according to Earle. The investments have brought focus on the use of green water in combination with blue water. Water that flows either above or below ground is called ‘blue water’. This water is used for irrigation. ‘Green water’ is water that is absorbed and temporarily stored in soil after rain that falls directly on fields “Only occasionally has the natural supply of rainwater been factored into policy solutions, even in areas where rain-fed agriculture has been the norm for as long as anyone can remember,” stated a 2018 article.

Extraction of blue water for irrigation has dried up lakes and groundwater aquifers (an aquifer is a host of groundwater) in the past. Water allocated for irrigation also competes with domestic water supply and sanitation provision. In the early 2020s the Zambezi river basin was already showing the way forward. TIARA had identified hotspots with farmers who enhanced rainfed agriculture practises by attracting innovative finance. The Zambezi Watercourse Commission joined the initiative to provide organisational support, and especially expand on its goal to provide increased livelihood support to rural populations.

Today, in 2050, the Zambezi Watercourse Commission is investing big to support rainfed agriculture across the basin’s eight countries.

Today, in 2050, the Zambezi Watercourse Commission is investing big to support rainfed agriculture across the basin’s eight countries.  In 2022, Earle noted that rainfed agriculture was seen as a little backward and traditional and that governments were viewed as more powerful if they pushed for large-scale irrigation schemes. The Transforming Investments in Africa’s Rainfed Agriculture (TIARA) project however, had not been shy of advancements in technology. The opposite, in fact. TIARA capitalised on enhancing existing rainfed agricultural practices such as terracing, mulching,

In 2022, Earle noted that rainfed agriculture was seen as a little backward and traditional and that governments were viewed as more powerful if they pushed for large-scale irrigation schemes. The Transforming Investments in Africa’s Rainfed Agriculture (TIARA) project however, had not been shy of advancements in technology. The opposite, in fact. TIARA capitalised on enhancing existing rainfed agricultural practices such as terracing, mulching,